- Paraiba

- Ruby

- Sapphire

- Emerald

Paraiba is Brazil’s most sought-after intensely saturated Windex-colored tourmaline variety. Over the years, the term Paraiba has come to signify the most desirable and expensive of all gemstones, on par with rubies, sapphires, and emeralds.

Paraiba gems first appeared on the market in the 1980s, creating a stir with their stunning electric-blue color and supercharged appearance. Paraiba immediately joined the exclusive club of high-octane rarified gemstones such as Burmese rubies, Colombian emeralds, and Kashmir sapphires.

The luminescent copper and manganese-colored gems were named after the Brazilian state of Paraiba, where they were discovered. Deposits of similar color tourmaline separated from Brazilian deposits by continental drift millennia ago were discovered in Nigeria and Mozambique.

It is easy to find a diamond that suits your desire, but looking for a particular Brazilian Paraiba is a waste of time because the exhausted mines have nothing coming out of the ground. Unlike diamonds, available in virtually any size and grade, Paraiba has always been in short supply, particularly in the finest qualities, no matter how much money is offered.

Buying Paraiba

Because of its rarity, you can come across Paraiba jewelry only at high-end jewelry stores such as Graff or Winston or at the auctions such as Christie’s or Sotheby’s.

Leon Mege is the pioneer behind using this rarest and most sought-after gemstone in jewelry, and the House of Leon Mege is your best source to hunt down this magnificent gem. Please call us at (212) 768-3868, and we will work with you to source and set Paraiba into a one-of-a-kind custom-designed mounting.

Leon Mege is a purveyor of fine gemstones and has been in business for over four decades. Maestro Mege creates beautiful, contemporary jewelry featuring incredible gemstones from around the globe. We ethically source the finest and rarest gemstones from a small number of well-established wholesale gem dealers, personally vetted by Leon Mege.

Paraiba origin

The Brazilian Paraiba, one of the most coveted gemstones, was discovered in the early eighties by a gem hunter Heitor Dimas Barbosa, who found a deposit near the village of Sao Jose de Batalha in the northern part of Paraiba state of Brazil. A decade later, other mines were found in the north of Paraiba state and the south of Rio Grande de Norte, next to the Paraiba state.

The blue-green Paraiba tourmalines were later discovered in Mozambique and Nigeria. Mozambique tourmalines have less copper and a lighter color than a typical Paraiba from Brazil. The Nigerian gemstones don’t have the same vivid saturation as the Brazilian material.

Why is Paraiba unique?

There are so few Paraibas in the world that only a single Paraiba is found for every 10,000 diamonds, making Brazilian Paraibas so scarce that collectors and jewelry lovers have to hunt them down.

These gemstones are valued for their scarcity and unique neon color. The presence of copper in Paraiba tourmalines gives the gem its ethereal, radiant blue hue. To be called “Paraiba,” a stone must have some copper content detected using a spectroscope. A general absorption starting at 600 nm identifies the stone as a cuprian elbaite tourmaline.

Another tourmaline species, the Cuprian-bearing liddicoatite found in Mozambique, has similar color and concentrations of copper and manganese as elbaite tourmaline.

Natural color

Paraiba tourmalines naturally come in many colors, including blue, pale green, purple, and violet. Practically all Paraiba tourmalines are gently heated to release their intense color. Since antiquity, heat treatment has been commonly used to enhance the color of many gemstones. Other varieties of tourmaline, such as rubellite and rubies, sapphires, tanzanites, beryls, zircons, and other gems, are also routinely heat treated.

The heating is done using special equipment which gradually increases the temperature to about 500-700F over hours and sometimes, even days. The regular, high-heat treatment leaves identification marks in the gemstone crystal structure, while low-heat does not. The general assumption is that all Paraibas are heat-treated, although, theoretically, the heating could naturally occur.

Paraiba characteristics

The Paraiba tourmalines are cut to maximize the weight and preserve the volume. You should not expect perfect symmetry and ideal proportions from Paraiba. The most valuable properties are the color hue, saturation, and material transparency. The Paraiba is a “Type III” gem, meaning visible inclusions do not significantly affect its value. The color hue and saturation are much more important. Translucent and opaque Paraibas are usually fashioned into cabochons (cabs) – a button-like shape.

Cleaning and care

All tourmaline varieties are relatively durable gemstones that can withstand daily wear. Paraiba variety is typically more included and should not be exposed to harsh chemicals, immersed in an ultrasonic cleaner, or steamed. Instead, use mild soap and warm water to gently brush the piece with Paraiba and dry thoroughly with a lint-free cloth. Each Paraiba piece should be stored individually in a separate box or a pouch because other jewelry can scratch Paraiba.

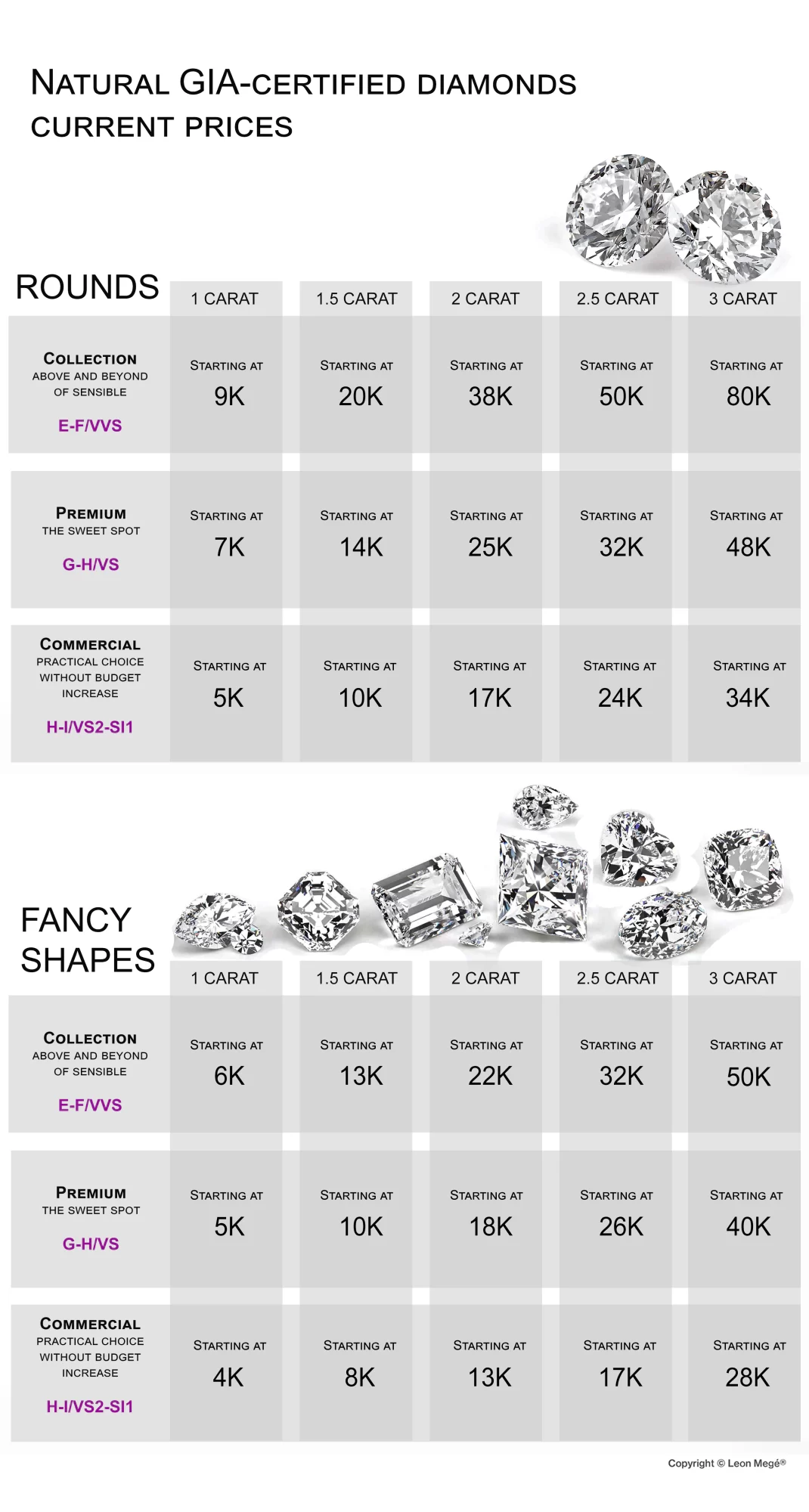

Paraiba’s prices

It depends on the gem’s color saturation, clarity, and origin. The finest Brazilian Paraiba can fetch up to 100K per carat. On the other hand, African translucent cabs or pale-blue faceted gems are often sold for a few hundred a carat. Below are a few examples of the record-breaking Paraiba sales (all prices in USD):

June 16th, 2022 – a 10.31-carat Brazilian Paraiba was sold at $1,197,000 at Sotheby’s New York.

May 29th, 2018 – a pair of 7.46-carat and 6.81-carat pear-shaped Brazilian Paraiba eardrops fetched $2,7 million or almost $200,000 per carat at Christie’s Hong Kong.

The Ethereal Carolina Divine Paraiba claimed to be the world’s largest Paraiba gem, is a 191.87-carat pale-blue oval set in a horrible and tacky Paraiba Star of the Ocean Jewels necklace by the Canadian jeweler Kaufmann de Suisse. In 2014 the massive 36.44 by 33.75 mm gem was offered for sale at the Kaufmann de Suisse boutique in Montreal for $100 million. We estimate the gem’s worth around $7 million loose, or $3 million in the necklace.

May 25th, 2022 – 3.81 carats oval Brazilian Paraiba tourmaline to be sold for approximately $300,000 at Christie’s Magnificent Jewels live auction.

June 22nd, 2022 – a brilliant-cut Brazilian Paraiba tourmaline weighing 5.09 carats is predicted to sell for up to $484,000 during the Bonhams Hong Kong Jewels and Jadeite auction.

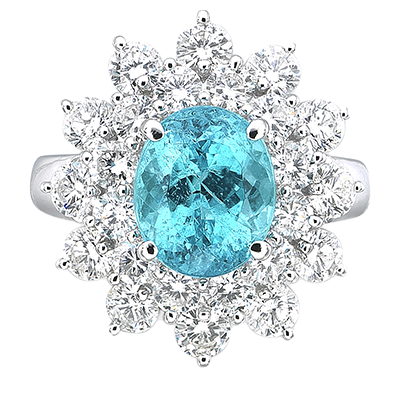

Paraiba in jewelry

When the evening sun is slowly sinking into the sea behind the domes of Santorini churches, the island transforms itself into a floating jewel encrusted with Paraibas. Traditional jewelry houses, such as Bulgari, Cartier, and Harry Winston, have all included Paraiba in their high jewelry collections.

Leon Mege’s award-winning Paraiba jewelry is highly regarded by industry experts, fashion critics, editors, curators, and bloggers as unique works of art. In 2015, Leon Mege was honored with the most prestigious jewelry award – the AGTA “Best Of The Show” for his Paraiba cab-and-French-cut diamond ring.

Paraibas of exceptional quality should be handled respectfully due to their exclusivity and value. Tourmaline ranks 7.5 out of 10 on the Mohs hardness scale, making it reasonably hard for use in jewelry with certain precautions. A Paraiba worn on a finger will eventually sustain slight-to-moderate abrasion and minor chipping. Repolishing such a stone can be dangerous and potentially disastrous.

We recommend setting faceted stones into pendants, necklaces, and earrings where precious Paraiba is relatively safe from the hard knocks a ring would sustain. Cabs are much more practical for casual wear and are recommended for rings. Many translucent Paraiba cabs feature natural inclusions of copper, which have a shimmering effect when the light hits them, resembling “aventurescence,” gemstone phenomena. The glistening Paraiba cabs are stunning, lending themselves to unorthodox jewelry designs that stand out.

Setting a Paraiba tourmaline into dark metals such as antiqued white gold or silver helps to accentuate its color. Paraiba could be combined with green, yellow, and purple gemstones and looks stunning against white or yellow diamonds.

African Paraiba

The name “Paraiba” became an issue in the early 2000s when the discovery of a copper-bearing tourmaline in Africa with a similar color and properties to Brazilian material was made. The legitimacy of using the “Paraiba” name for the newly found African material was hotly disputed. Still, political correctness prevailed, and now it is perfectly legal to call any blue-to-green copper-bearing tourmaline “Paraiba” regardless of its origin.

Some gem dealers still insist on calling African tourmaline “Paraíba-type” or “cuprian elbaite,” but most refer to the material as Paraiba. Today, almost all Paraíba tourmaline comes from Africa, making Brazilian gemstones rare, desirable, and extremely valuable. A Paraiba certified to have Brazilian origin by a reputable gem lab costs 10 to 100 times more than nearly identical stone mined in Africa.

The chemical differences between Brazil, Nigeria, and Mozambique tourmalines are small. Some Mozambique tourmalines are lighter because they have less copper, which gives Paraiba its unique color. Brazilian Paraiba colors are more intense, while Mozambique has the widest range of hues.

The name “Paraiba” became an issue in the early 2000s when the discovery of a copper-bearing tourmaline in Africa with a similar color and properties to Brazilian material was made. The legitimacy of using the “Paraiba” name for the newly found African material was hotly disputed. Still, political correctness prevailed, and now it is perfectly legal to call any blue-to-green copper-bearing tourmaline “Paraiba” regardless of its origin.

Some gem dealers still insist on calling African tourmaline “Paraíba-type” or “cuprian elbaite,” but most refer to the material as Paraiba.

Today, almost all Paraíba tourmaline comes from Africa, making Brazilian gemstones rare, desirable, and extremely valuable. A Paraiba certified to have Brazilian origin by a reputable gem lab costs 10 to 100 times more than nearly identical stone mined in Africa.

The chemical differences between the tourmalines from Brazil, Nigeria, and Mozambique are small. Some Mozambique tourmalines are lighter because they have less copper, which gives Paraiba its unique color. Brazilian Paraiba colors are more intense, while Mozambique has the widest range of hues.

Paraiba tourmaline’s electrifying color gave birth to claims of its supernatural abilities to protect its owner against negative mental, spiritual, emotional, and even physical forces. Researchers at Leon Mege Paranormal Institute of Gemology (PIG) in Princeton, MS, recently discovered that wearing Paraiba will protect against a political opponent. Hillary Clinton allegedly refused to wear a Paraiba-set ring before the elections, claiming it did not work with her skin tone, and we know what happened next. Our PIG scientists are conducting human experiments testing a theory that Leon Mege mounting can intensify the protective power of Paraiba. Please let us know if you are willing to volunteer for the studies or perhaps donate your brain.

Ruby is a red variety of mineral corundum. All other corundum colors, including pink, are called sapphires. Rubies are by far the most precious gemstones that are stunning to behold and rarer than diamonds. Ruby’s vivid color was frowned upon in the drab ’70s. Today red is a badge of solid personality, intellect, and success. Rubies are a true statement of personal style and sophistication.

The diamond market is controlled by De Beers Société Anonyme, manipulating the market supply and controlling the prices. Rubies do not have an international monopoly to lean on. Therefore, the perception that diamonds are rarer than rubies is not accurate.

Corundum crystals are found in nature in every color and even completely colorless. Sapphires and rubies are the same stones colored by different impurities.

- Mohs’ Hardness: 9

- Specific Gravity 3.97-4.05

- Chemical Composition Al2O3

- Refractive Index: 1.762–1.774 (0.008) Uniaxial negative

- Crystal System: Hexagonal (trigonal); dipyramidal structure, barrel-shaped, tabloid-shaped

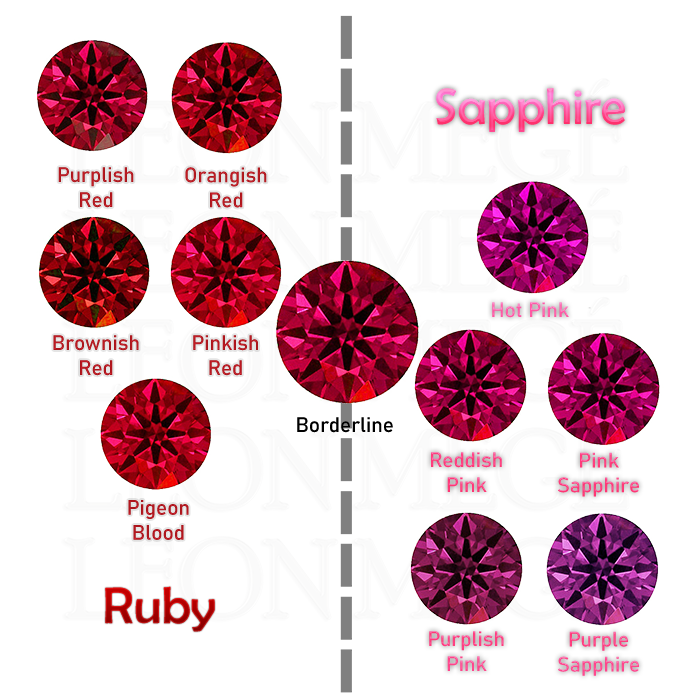

Ruby vs. Pink sapphire

Rubies and pink sapphires are distinguished by the saturation of the red hue and the strength of blue and yellow undertones. The presence of chromium causes the color of a ruby, while a combination of chromium and iron causes the color of a pink sapphire. Chromium, iron, or titanium impurities are responsible for most color variations. Rubies and pink sapphires can be distinguished by their clarity. Rubies tend to have more imperfections than pink sapphires. Rubies are more valuable than pink sapphires. This is because rubies with a saturated pure red color are extremely rare.

Pigeon Blood rubies

Exceptional rubies with a pure red color are the most coveted gems. They are known as “Pigeon Blood red” rubies that, aside from their distinct color, invariably are stones of superior quality.

“Pigeon Blood” is a historic term used for centuries by the jewelry trade to describe the finest rubies from the Mogok mine in Burma (Myanmar). For a ruby to qualify for the term “pigeon blood red,” the color must be an intense, saturated, and uniform red with vivid internal reflections. Their saturated red color without a hint of blue or brown is intensified by strong fluorescence caused by a lack of iron impurities.

Any treatment (heating, fissure filling, etc.) disqualifies a stone from being described as “pigeon blood red.” The stone must be a transparent crystal without eye-visible or dark inclusions. In addition, it must show a homogeneous color distribution with vivid internal reflections.

Burmese rubies ban

The international trade in valuable Burmese rubies and jadeites has been under political sanctions since 2003, aimed at applying pressure on the communist junta. The embargo banned all gemstone imports from Burma with one loophole – stones could be legally imported if polished outside Burma, usually Thailand. In 2008 the Bush administration introduced legislation banning Burmese ruby and jadeite trade regardless of processing location.

With the normalization of relations between the US and Burma in 2012, the Treasury and State Departments announced that they were lifting sanctions on a range of Burmese products, but not ruby and jadeite. However, in August 2013, President Obama signed an executive order that renewed the ban on importing Burmese ruby and jadeite for another year. Finally, in October 2016, President Obama signed an executive order to lift all remaining Burma sanctions, including the Burmese ruby and jade ban.

However, after ten years of democratically elected governments, the military in Myanmar arrested the democratically elected government, declared a state of emergency, and handed all powers to the army chief.

In 2021 the Biden administration banned US companies from dealing with three Myanmar gem producers associated with the Burmese junta: Myanmar Ruby Enterprise, Myanmar Imperial Jade Co., and Cancri Gems and Jewellery Co. The sanctions did nothing to the Burmese junta supported by Chinese and Russians who keep buying ruby and jadeite at Myanmar government gem auctions. Most of Myanmar’s Burmese rubies and sapphires are smuggled into Thailand to be cut and sold on the international market, and no embargo can change that.

Unheated gem rubies over 6 carats are exceptionally rare and command record prices. Burmese rubies are the rarest and most valuable. Top color stones from Madagascar, Tanzania, and Mozambique are beautiful but cannot compete with Burma rubies in terms of value.

Unlike diamonds, rubies are valued for their transparency. Occasional inclusion, even one you can see, is usually not a deal-breaker as long as the rest of the stone is crystal clear.

The price of a ruby is in direct relation to the rarity and quality of the stone.

Leon Mege, acting as your buying agent, will work directly with the most reputable gemstone dealers worldwide to guarantee the best value in the market.

The average 3-5 carat ruby ranges in price from hundreds of thousands to several hundreds of dollars per carat depending on its origin, treatment, color, clarity, and cut.

A top-color unheated Burma ruby can fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars per carat at an auction. A heated ruby of the same size and color will cost tens of thousands per carat. A too light or too dark heated, poorly cut, heavily included ruby with tint will cost only a few hundred per carat. A reconstituted or glass-infused ruby fetches a few dollars per carat. Synthetic rubies and red spinel used as ruby substitutes in cheap jewelry are practically worthless.

For centuries before scientific tools for gem identification were invented, red spinels and rubies were often confused. For example, the famous Black Prince’s Ruby in the British crown turned out to be a spinel when custodians took it out during cleaning.

Spinel is a magnesium aluminum oxide, while ruby is aluminum oxide. In ancient times the red spinels came from Balascia or Badakhshan in Northern India, where the name “Balas Ruby” originates.

Called “Geneva rubies” and sold by an unknown merchant in 1880, they were the first known rubies produced by flame fusion. Twenty years later, Auguste Verneuil developed a special furnace for making synthetic rubies on a large scale. Most people do not realize that synthetic rubies can be that old. They are stunned to find out that grandma’s 100-year-old ruby is a worthless fake. Synthetic corundum is very cheap, easily identifiable, and never used in fine jewelry.

Injecting molten leaded glass under high pressure into heavily included rubys’ fractures turns nearly opaque stones transparent. The treatment is not permanent and can be easily damaged. Glass-infused rubies are brittle and have no value, but they look more natural than synthetics. Leaded glass is a toxic substance that can affect health.

Colorful corundum

Corundum crystals are called sapphires, except for the red variety called ruby. Blue sapphires owe their color to traces of iron contaminating the crystals. They are the best-known and some of the most coveted precious gemstones. Sapphires come in a rainbow of colors: pink, orange, yellow, purple, green, and black. The word Sapphire comes from the Latin “sapphirus,” which Romans used for lapis lazuli, a blue marble-like gemstone. Fancy-colored sapphires have their name preceded by a specific hue, for example, “yellow sapphire.” Traditionally, the word “sapphire” alone refers to a blue variety.

Corundum is the scientific name of the mineral.

Mohs’ Hardness: 9

Specific Gravity: 3.95-4.00 Sapphire

Chemical Composition: Al₂O₃ aluminum oxide

Refractive Index: 1.762–1.774 (0.008) Uniaxial negative

Crystal System: Hexagonal (trigonal); dipyramidal structure, barrel-shaped, tabloid-shaped

Sapphires are rare and popular

Natural sapphires and rubies are much rarer than diamonds. There are only a few locations that produce gem-quality sapphires. Unlike diamonds found virtually everywhere, the finest sapphires are found only in a few locations along the narrow crescent-shaped corridor stretched between modern-day’s Tajikistan and Nigeria.

The right conditions for sapphire formation occurred at 6 to 18 miles depths where corundum crystals grew out of cooling molten rocks and were carried to the surface by erupting volcanos. It happened roughly 150 to 200 million years ago in a single area of prehistoric landmass called Gondwanaland, eventually torn apart by continental drift. This split sapphire-rich regions between the Indian subcontinent, Sri Lanka, Madagascar, and Africa, where the top-grade sapphires are found today.

Sapphires are on the rise due to the following:

- Improvements in their identification and grading

- Dwindling supplies of rough

- Political and military instability in regions producing the best stones

- The rise of Asian markets where sapphires are historically more popular

- Eroding diamond prestige

Sapphire value by location

- Kashmir

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

- Madagascar

- Tanzania

- Tajikistan/Afghanistan

- Montana

- Thailand

- Vietnam

- Australia

Most valuable sapphires

The most valuable sapphires are naturally occurring varieties with no signs of artificial treatment. Sapphire origin has the most significant influence on price, more than the color grade. Each locale produces a distinct type of stone whose origin can be determined by its chemistry, inclusions, and hue. The scarcity of stones from a specific region means the price of the old material is not affected by new production at other locations. Sapphire’s essential properties are the color strength, color saturation, and purity of its dominant hue. Blue is the most desirable sapphire color; the top grades are “Royal Blue” and “Cornflower Blue.” The Padparadscha is an extremely rare sapphire color. It has a mix of pink and orange hues. Other valuable sapphire hues are pink, purple, orange, and yellow. Brown, green, and colorless sapphires are the least desirable.

The finest blue sapphires hail from Kashmir, the place serenaded in Led Zeppelin’s hit song. The mine is long exhausted from centuries of digging, so Kashmirs on the market come from vintage pieces and are sold at auctions. Burmese sapphires are next on the list. All of the finest Burmese material in the world comes from a single mine that goes hundreds of feet deep and makes a weird curve underground. Another mine produces material that has to be enhanced by heating. The finest specimens from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) are also extremely valuable. Less desirable blue sapphires come from Madagascar, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, and Thailand.

Collectors value pastel-colored Montana sapphires for their origin despite the drab appearance and bleak hues. The rest of the world – Nigeria, Australia, Vietnam, Laos, Pakistan, Brazil, and Colombia produce an occasional gem, but mostly low-grade junk used in cheap jewelry.

Padparadscha Sapphires

Peachy-orange sapphires with creamy pink overtones are precious and extremely rare. They are only found in a few places around the world, including Sri Lanka, Madagascar, and Tanzania. The word itself comes from Sanskrit and refers to the color of a lotus flower. The color, caused by the presence of traces of iron and chromium, is poetically described as amber, salmon, beer, and pink roses all in one.

Kashmir sapphires

Kashmir is the finest variety of blue sapphires valued for their scarcity, deep hue, and velvety texture. The Kashmir sapphires originate from Kashmir Valley mines in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. They were found in the 18th century but were depleted in the early 19th century.

The Kashmir sapphires make regular appearances at the auctions such as Christy’s and Sotheby’s, where they command astronomical prices. Kashmir sapphires are also found in museum collections.

Montana sapphires

Montana’s native Yogo sapphire was accidentally discovered by a gold miner in the 1890s. Let’s face it these sapphires are not the prettiest ones. They would be thrown out with waste soil at any mine in Asia. But in the US, they ride on the wave of patriotism and sleek marketing. Montana’s sapphire production is minuscule compared to other sapphire-producing countries. The Montana sapphires are available in a kaleidoscope of hues, ranging from deep blues to vibrant greens, rich yellows, and breathtaking bi-colors. Most of the Montana sapphires come in pale pastel colors and inky hues. Yogo sapphire’s origin can be considered igneous, unlike most sapphires that are a product of metamorphic formation. They have unique inclusions and distinct trace elements, making them readily distinguishable from sapphires mined at other locations. The Phillipsburg mines are open to the public, and you can try your luck looking for stones after paying an exorbitant entrance fee.

How the sapphire origin is determined

Gemstones from certain locations command premium prices because they have a particularly beautiful and unique appearance. Inclusions are among the most important clues in determining a country of origin. There are unique types of inclusions found at specific localities. For example, pargasite or tourmaline crystals have only been identified in Kashmir sapphires. Uranpyrochlore inclusions are found only in Cambodian or Vietnamese material. Kashmir’s “silk” is tiny needle-like inclusions suspended throughout the crystal, scattering the light and giving the stone a soft, velvety appearance.

Fluorescence can be helpful. Sapphires from Sri Lanka exhibit fluorescence with greater regularity than other sapphires. Its presence points toward its origin. Growth patterns and color zoning are additional clues. Whether the rough crystals are rounded or sharp is more typical in some locations but not others. Kashmir sapphires exhibit sharp-bordered zones of blue and milky white. Madagascar’s Antsiranana sapphires often display blue-violet, greenish-blue, and greenish-yellow color zones. Spectrophotometry and energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence can detect a unique chemical growth mix indicating a specific deposit. Kashmir’s iron level is typically low, but Cambodian sapphires often show very high iron concentrations.

Phenomenal sapphires

Phenomenal sapphires are valued on the phenomena’ prominence rather than the strength of the dominant color.

- Color-change stones – typically blue to green or blue to purple

- Stones with asterism (star sapphires)

- Gems with chatoyancy (cat’s eye)

Sapphire lore

Sapphires were known to the Etruscans at least seven centuries before Jesus. In the 13th century, Marco Polo described sapphires in great detail in his “Book of Marvels” while visiting the Island of Serendib (Sri Lanka). Sapphire was a favorite gem of medieval royalty who believed a sapphire could protect them from harm, envy, and uprising.

By the Renaissance, sapphires were coveted by the wealthy and influential for their ability to prevent poverty and increase one’s IQ. It is September’s birthstone and commemorates the 5th and 45th anniversary. For several reasons, sapphires are on the rise today.

- Modern identification and grading are greatly improved

- Dwindling supplies of rough and lack of discoveries

- Political and military instability choke the supply

- The rise of Asian markets where sapphires are historically more popular

- Eroding diamond prestige

- TikTok generation craves color

Sapphire engagement rings

As soon as sepia-colored Dorothy crash-landed into Munchkinland’s Technicolor, diamond reign began to crumble. The age of monochrome photos and black-and-white movies gave way to the world of brilliant colors on-screen, in life, and jewelry. Princess Diana’s sapphire engagement ring (later re-gifted to Kate Middleton) was a turning point for sapphire acceptance as a legitimate diamond replacement for engagement. As a result, it took a tremendous marketing effort by DeBeers to prevent diamonds’ popularity from crashing. While sapphires are extremely hard, they are less durable than diamonds and most likely will get scratched and chipped over time. Sapphire can be repolished to regain a brand-new look. A halo or a diamond cluster can protect a sapphire set in a ring. Cabochons are a safe bet for those less protective of their jewelry.

Treatments and enchancements

Only a handful of mines worldwide produce sapphires of striking color and clarity that need not be treated. These gemstones are rare and usually certified by a gem lab to have natural color. Turning translucent colorless pebbles into sapphires using heat is an ancient practice widely accepted as non-detrimental to the stone’s nature. However, the heating temperatures and the potential use of additives dramatically affect the stone’s value. Briefly subjecting a sapphire to mild heat to dissolve and reconstitute rutile inclusions is common. In fact, most world’s sapphires are treated with moderate heat, not affecting their crystal structure. In nature, a forest fire or volcanic activity can have a similar effect. Sapphire’s color after heat treatment is permanent, irreversible, and not considered artificial.

It is impossible to identify a treatment by looking at the stone. Experienced dealers are able to distinguish slight color variations to form an opinion, which is nothing more than an educated guess. In general heated and natural stones have exact same luster and brilliance. Only color zoning is a dead giveaway that the stone is unheated.

A reputable gem lab certificate is the best way to learn about potential treatments. A certificate from a gem lab such as Gubelin, AGL, GRS, or SSEF should accompany any valuable sapphire.

Clarity or color enhancement by heat is categorized into the following grades:

– H – Enhanced by heat (no residues present)

– H(a) – Enhanced by heat – insignificant residues within fissures only.

– H(b) – Enhanced by heat – minor residues within fissures only

– H(c) – Transitional grade between H(b) and H(d). Residues of glass-like materials are present in cavities and/or in fissures. – H(d) – significant and deep-reaching residues present within fissures and cavities filled with lead glass (also known as “Composite Ruby”)

– H(Be) – Enhanced by heat and light elements (such as beryllium).

– PHT (HPHT) – Enhanced by pressure and high temperature (PHT).

– E – minor residues of foreign solid materials may be present within fissures and/or cavities.

Low-grade sapphires are heated to induce better color and improve clarity.

Flux treatment

Heavily included material can be heated several times in the presence of fluxing agents – borax, sodium carbonate, and sodium silicate. The chemicals do not alter the stone chemistry but interact with inclusions in the crystal, improving clarity and color. A good example is the Geuda from Sri Lanka which looks like a piece of dirty marble when it comes from the ground but turns clear and blue after the treatment.

Surface diffusion

Coating colorless sapphires with titanium before subjecting them to a very high temperature produces an intense blue color. The penetration is usually shallow, and the stone cannot be recut without losing color. This treatment is mainly used on faceted stones.

Lattice or bulk diffusion is induced by low heat in the atmosphere of beryllium vapors produced by adding natural chrysoberyl to the crucible. Light yellow or pink sapphires s infused with beryllium turn into padparadschas. Diffusion treatment is not an acceptable enhancement.

Low-pressure heating

HT+P sapphires are heated at high temperatures under low pressure. As a result, these stones have durability issues. They require separate disclosure under the category of HP. The treatment must be disclosed to consumers using clear language, for example, “sapphire treated with heat and pressure.”

Any naturally occurring red corundum is called a ruby. What is called a red sapphire is a colorless corundum (leucosapphire) infused with beryllium, turning red under intense heat and pressure.

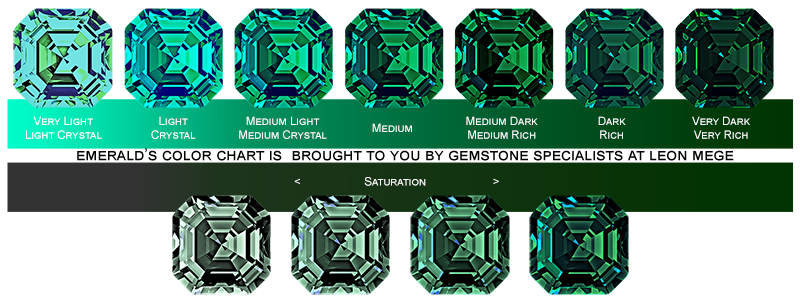

Emerald Color Is The Most Important Factor

Emeralds are members of the elite club of precious gemstones, along with Burmese rubies, Kashmir sapphires, and Brazilian Paraibas. Their color has the richness and opulence of a blooming tropical forest. Emeralds have been synonymous with green color since antiquity.

Emeralds are members of the elite club of precious gemstones, along with Burmese rubies, Kashmir sapphires, and Brazilian Paraibas. Their color has the richness and opulence of a blooming tropical forest. Emeralds have been synonymous with green color since antiquity.

Egyptians were mining emeralds as early as 3500 BC. According to the Bible, it was one of the four precious stones Elohim gave King Solomon. Egypt was the only source of emeralds until the 16th century when the murderous Spanish conquistador’s conquest of South America led to the discovery of modern-day Colombia.

Beryl crystals formed in hydrothermal veins from mineral solutions contaminated with impurities responsible for various beryl colors. Beryl is a cyclosilicate with the chemical composition Be3Al2 (SiO3)6.

Variety: Emerald

Species: Beryl

Mohs Hardness: 7.5 to 8 out of 10

Color: Medium-light to dark green, slightly yellowish-green, and bluish-green

RI: 1.577 to 1.583 (+/-0.017)

Birefringence: 0.005 to 0.009

SR/DR/AGG: DR

Clarity Type: Type III

Optic Character: Uniaxial negative

Pleochroism: Moderate to strong green & bluish green

Spectrum: Broad absorption at 580 to 630nm. Lines at 646 & 662nm. Distinct lines at 680.5 & 683nm. Almost complete absorption of the violet.

Fluorescence: Generally inert. However, top colors may fluoresce orangy-red to red under LW & SW (stronger reaction under LW)

SG: 2.72 (+0.18 / -0.05)

Routine Treatments: Oil is a traditional treatment that is generally accepted as natural.

Additional Enhancements: Excessive oiling, fracture filling, fracture filling combined with dye

Extremely rare, top-quality Colombian emeralds are 400 times rarer than diamonds and cost more per carat. The vivid green is not the rarest Beryl variety. That distinction goes to red beryl, called bixbite. The historical values of Colombian emeralds demonstrate a continuous and uninterrupted increase in net worth of approximately 5-10% annually. Every year miners dive deeper into the elusive emerald-bearing veins to bring an increasingly shrinking supply of gems to the market.

Setting emeralds

The choice of setting depends on whether the emerald is worn in a ring, earrings, or necklace. Wearing an emerald in a ring can easily cause it to chip or scratch. A halo or cluster of diamonds surrounding an emerald will absorb the hard knocks and protect the stone.

An emerald can be set in a bezel that wraps its girdle for better protection. Setting an emerald in a bezel is riskier than using prongs.

Also, bezel-set stones are harder to clean or unset for repolishing without destroying the mounting. Claw prongs provide sufficient protection for emeralds.

V-prongs do not offer any advantage when setting emeralds. It’s the opposite – setting the emerald tip into a V-prong carries more risk.

An emerald’s color often improves when it is set in yellow gold. Top-color stones are always set in platinum. Soft metals like 22K gold and pure platinum are used to make prongs when setting rare and expensive emeralds.

Emerald color

The most-prized emerald color is evenly distributed, vivid bluish-green without significant color zoning. A medium tone with clear transparency is desirable but is subject to personal taste. The value drops if yellow or blue hues become too dominant. The bluish-green to pure green emeralds in medium to slightly dark tones are the most desirable. The strength, intensity, and even distribution of color are more important than the tone. The best emeralds have vivid saturation and high transparency.

Where do emeralds come from?

The best and most valuable emeralds come from Colombia. Colombian emeralds were created millions of years ago during the formation of the Andes Mountains. The mineral-rich water seeping through the cracks between rock layers solidified into emerald-bearing veins. The most famous emerald deposit is the Muzo mine, just northwest of Bogota. Besides Colombia, emeralds are found in Brazil and Zambia, while Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Australia, Pakistan, and Russia have less important deposits. There are several major emerald deposits In Brazil: Minas Gerais, Bahia, and Goias.

Colombian mines

Colombian emeralds are mined in the area known as the Emerald Belt of the Cordillera Oriental in the Gobernación de Boyacá and Cundinamarca district. Since the 1500s, the three main emerald mines in Colombia have been Muzo, Coscuez, and Chivor. The most famous is the Muzo mine, which produces the world’s most prized emeralds. The other two mines are Chivor, which produces lighter, slightly more blueish material, and Coscuez, which has warmer shade stones.

Muzo emeralds

Muzo emeralds

This color is typically a vivid green. A butterfly (mariposa in Spanish) lives only in the Muzo area and has the same color. Muzo crystals do not form clusters or aggregates. They tend to be shorter than those from Chivor.

Coscuez Mine

Coscuez crystals frequently occur as aggregates with multiple terminations. The crystals from Coscuez are longer than those from Muzo but shorter than those from Chivor. They have good transparency with a bright yellowish-green color but cannot be traced to the Coscuez mine by color alone. The inclusions are typically diffused and poorly defined.

Chivor Mine

Chivor emeralds are famous for their color and brilliance, even in dim light. Their crystals are elongated and do not form clusters or aggregates.

They generally have a lighter bluish-green color and fewer inclusions. They have three-phase inclusions containing gas, fluid, and crystals of halite, pyrite, and albite.

Top grade emeralds

Best emeralds are nearly void of inclusions and characterized by rich green color and high brilliance. The most desirable color for an emerald is a rich, bluish-green without a yellowish or brownish tint. They are not treated with oil and are accompanied by at least one certificate from a reputable gem lab in New York or Switzerland. Top-grade emeralds command the highest prices but are also more valuable and durable.

Colombian emeralds are the standard against which all other emeralds are usually compared. They are legendary for their deep color, with just the right amount of blue and yellow. Colombian emeralds command higher prices than emeralds from any other localities. A pair of the rarest and most expensive emeralds, the extraordinarily well-matched Grand Muzos weighing 23.34 and 23.18 carats, sold in 2019 for $4.5 million, thanks to continued demand for Colombian emeralds of the top grade with richly saturated uniform color.

Emerald vs. Beryl

Emerald and green Beryl belong to the same gemstone species but differ in color depth and saturation intensity. Green beryl owes its pale green color to the presence of iron impurities. Traces of iron can also be found in emeralds giving them a yellow and, sometimes, bluish secondary color. Iron is abundant near the Earth’s surface, but chromium which gives emeralds their beautiful color, is found 15 miles below the Earth’s crust. Beryl has to be directly exposed to chromium or vanadium during formation to become an emerald, a rare occurrence. Emerald’s refractive index is 1.565-1.602. Green beryl has a refractive index of 1.58-1.59.

Trapiche emerald

Trapiches are emeralds formed by inclusions separated into growth sectors radiating in a star-like fashion from the crystal’s core. The name trapiche comes from trapiche (de azúcar) meaning “sugar. Their spikes look like the grinding wheels used to process sugarcane in South America.

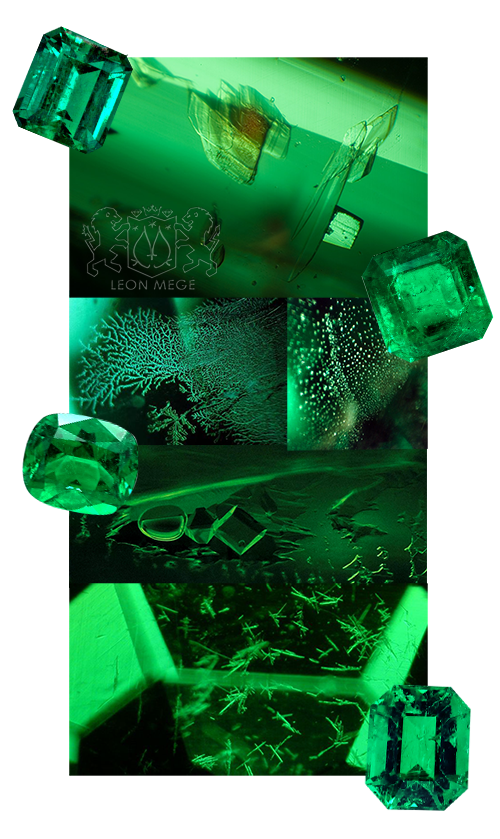

Emerald inclusions

Emeralds are type II gemstones, so inclusions are expected and are part of the crystal structure. Emerald’s inclusions do not diminish its beauty unless they are overwhelming and affect its appearance. Fewer visible inclusions make the stone more valuable. However, crystal-clear emeralds are incredibly rare and are called “High Crystal ” as opposed to High Color emeralds – pure in color but lacking clarity. High Color emeralds are bright beyond the wildest imagination, with amazing sparkle and scintillation.

Emeralds’ interior features, such as veils and wisps of natural imperfections that look like an overgrown, verdant garden, have been romantically termed jardin. Unlike diamonds, where clarity is essential to the stone’s value, inclusions in emeralds are expected. They are formed by gases and other minerals trapped inside an emerald during crystallization, and they are often viewed as desirable features aiding in emerald identification. Heavily included emeralds look cloudy and void of any brilliance. Areas of discoloration indicate potential crumbling of the surface. Emeralds with surface cracks extending over a third of the stone’s length are vulnerable and prone to disintegration.

Emerald grades and enhancements

The only legitimate types of emerald treatments are oil and liquid resin. Ninety-five percent of emeralds are enhanced with liquid resin, with the rest oiled with cedarwood oil extract. The advantage of liquid resin is that it is a more stable filler compared to oil. Both oil and liquid resin can be removed, although there is no reason ever to do that. Most oil-treated emeralds must be re-treated at some point, especially in hot climate zones. The high temperatures and atmospheric pressure will cause the oil to leak out, but not liquid resin, which is far more stable.

This is a judgment of the degree of clarity enhancement: minor (F1), moderate (F2), and significant (F3). “Minor” enhancement indicates the treatment has had only a slight effect on the face-up appearance, whereas “significant” indicates an obvious effect on the appearance.

99% of emeralds sold commercially would be classified as F3, which does not affect their value.

Emerald treatments

Clear emerald crystals are highly prized among collectors and connoisseurs. Unfortunately, an emerald without visible inclusions not treated with oil is a rarity. For centuries people used natural oil to infuse emeralds to conceal inclusions. Oil is the most accepted emerald treatment. When used in small quantities, it has a minor effect on the stone price. Using oil to fill fractures and cavities doesn’t change color. Oiling does not alter an emerald permanently and can be removed or evaporated over time.

Laboratories grade the presence of oil in emeralds as none, insignificant, minor, moderate, or significant. It is recommended to recertify an emerald at the time of the purchase to detect an oil treatment applied after a no-oil certificate was issued.

Emerald care

Emerald’s hardness of 7.5 to 8 on the Mohs scale is substantial, but because of small fractures and inclusions, emeralds can be brittle if knocked against a hard surface or subjected to extreme temperature change. Emerald’s hardness is not enough to protect them from scratching caused by everyday wear. Emeralds are cleaned by gently brushing with a soft-bristled toothbrush in warm, soapy water. Never soak emeralds in any cleaning solutions, or use an ultrasonic cleaner. If necessary, an emerald can be re-oiled.

Emerald metaphysics

Emerald is a May birthstone and Zodiac stone for people born between June 21st and July 22nd. According to Indian folklore, the word emerald is derived from Sanskrit Marakata, meaning “green as a plant,” and the Persian word smaragdus, meaning “green stone.” The Incas thought that emeralds foretell the future and reveal the truth.

Losing an emerald is bad luck. William Thomas Fernie’s 1907 book states, “Precious Stones for curative wear and other remedial uses likewise the nobler metals.” – “The falling of an emerald from its setting has been an ill omen to the wearer, even in modern times.”

Celebrities and emeralds

Emeralds have always been associated with royalty. Emeralds were Cleopatra’s favorite gemstone. In 1845, Prince Albert commissioned an emerald tiara for Queen Victoria featuring 19 pear-shaped emeralds, the largest weighing 15 carats. In 1911 Queen Mary wore an emerald choker that would later be given to Princess Diana as a wedding gift from Queen Elizabeth. John F Kennedy picked a Van Cleef & Arpels emerald engagement ring to propose to Jacqueline Bouvier in 1953. In 2011 Elizabeth Taylor’s emerald necklace was sold for $6.5 million at auction.

Emerald City

Is Emerald City real?

L. Frank Baum’s book, published in 1900, describes the Emerald City, where all residents were duped into thinking that the city was built of emeralds. They were required to wear green sunglasses they never took off. In the 1939 Wizard of Oz movie, the city was recast as a sparkling metropolis built entirely out of emeralds to take advantage of Technicolor.

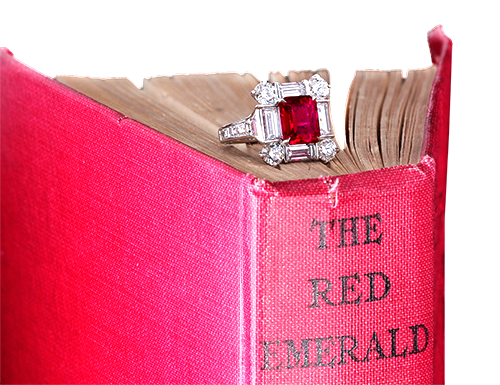

The Red Emerald

Bixbite is an extremely rare and gorgeous variety of red-colored beryl. For every 150,000 gem-quality diamonds, only one red beryl is found. Gem connoisseurs love it, and it is marketed as Red Emerald.

Sometimes raspberry-colored beryl from Madagascar called Pezzottaite or “Raspberyl” is passed on as bixbite. Pezzottaite is also very rare but less valuable than bixbite.

Emeralds and photography

Emeralds are the hardest stones to photograph; they are the most photoshopped gemstones. It is nearly impossible to take a picture that truly represents what you see in real life because digital cameras cannot capture the dynamic range of greens in emeralds. The same problem affects computer monitors as well. Emeralds are photographed using macro lenses, visually flattening the image and combining all inclusions into a single plane. Oil-filled fissures invisible to the naked eye become visible in the photograph, creating the appearance of a heavily included stone. A close-up picture of an emerald is not a fair representation of the stone’s actual appearance, making a presentation of an emerald via picture or a video truly challenging.