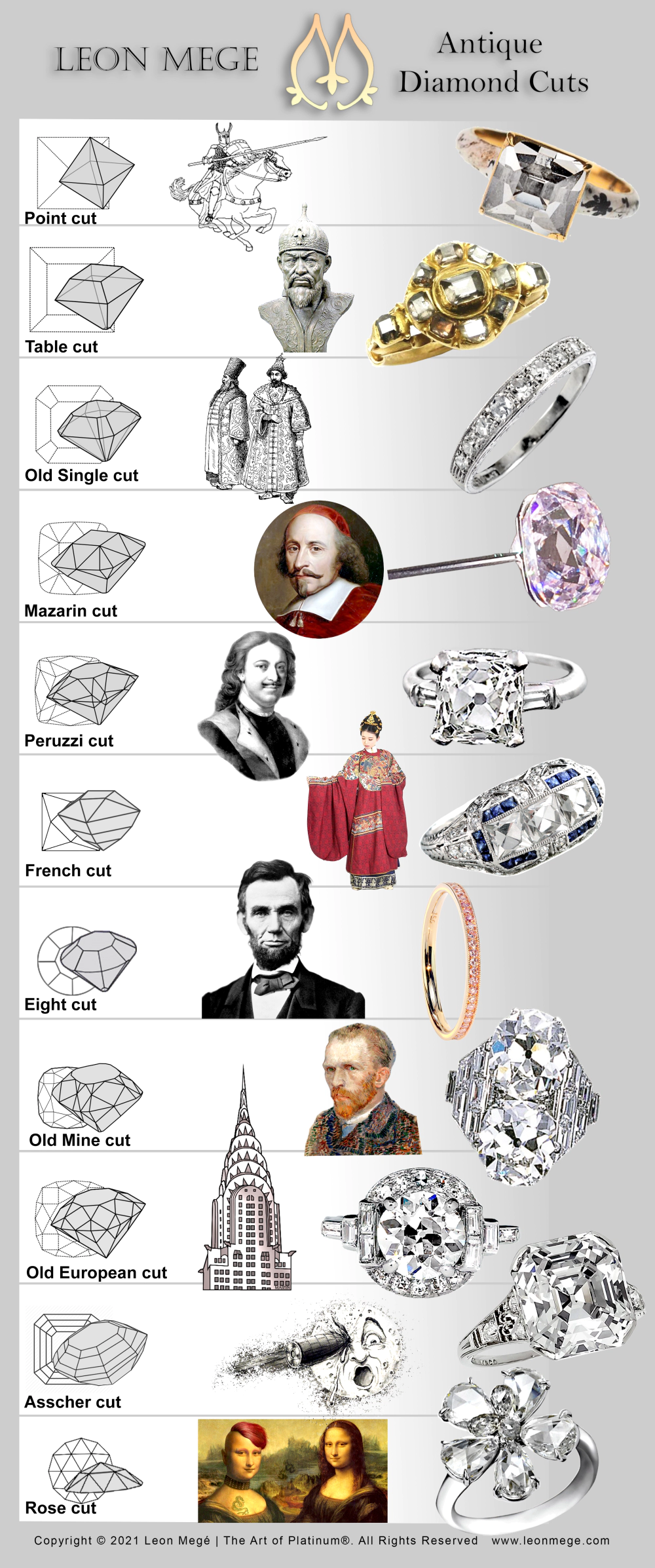

Most people are intuitively attracted to antique diamonds because vintage cuts have a distinctly retro vibe. Unfortunately, lab reports fail to differentiate between modern and antique cuts. Antique cushions are called Old Miners, and the antique rounds are Old Europeans. Other shapes are not as lucky; you must examine them to determine whether they have modern or antique faceting. True antique diamonds are scarce; they come from disassembled old jewelry. Most antique cut diamonds sold today are contemporary replicas. This fact does not diminish their beauty and value.

The most recognizable antique diamond cuts are:

Antique Advantage

Antique cuts are angelic orphans looking for a new home. They are steeped in fascinating history and charming traditions. Antique diamonds bring us closer to our roots, filling us with a sense of belonging to a bygone era.

Every antique diamond is unique. Their artisanal individuality makes up for mechanical precision. Antique diamonds were designed when candlelight was the primary source of indoor illumination, making them burst with intense fire.

Antique diamonds offer timeless romantic appeal and dazzling fire. Unlike modern cuts, there are very few antique diamonds to choose from. An antique Asscher cut is undeniably the most beautiful of all antique diamonds. It is closely trailed by Antique Cushions and Old European cuts. The classic French cut is the absolute classic among accent stones.

In popular culture, Carrie of “Sex in the City” says yes to Aidan’s proposal with a stunning Asscher-cut diamond ring after rejecting a pear-shaped diamond in a gold mounting.

When you compare a vintage diamond to a modern diamond, it’s easy to see the difference. Should the charming past radiating from every facet of an heirloom diamond be destroyed to increase the perceived value?

The answer is: No. Old cut stones are genuinely scarce and only get rarer with every passing day.

A recut diamond is identical to a diamond produced from rough yesterday. Without a historical record, it’s impossible to tell when the stone has been cut.

Unfortunately, many of the world’s most famous and historic diamonds have been recut over the centuries of their lifetimes. Sometimes it was done to improve the appearance of stones, but more often to conceal their identity for criminal gain.

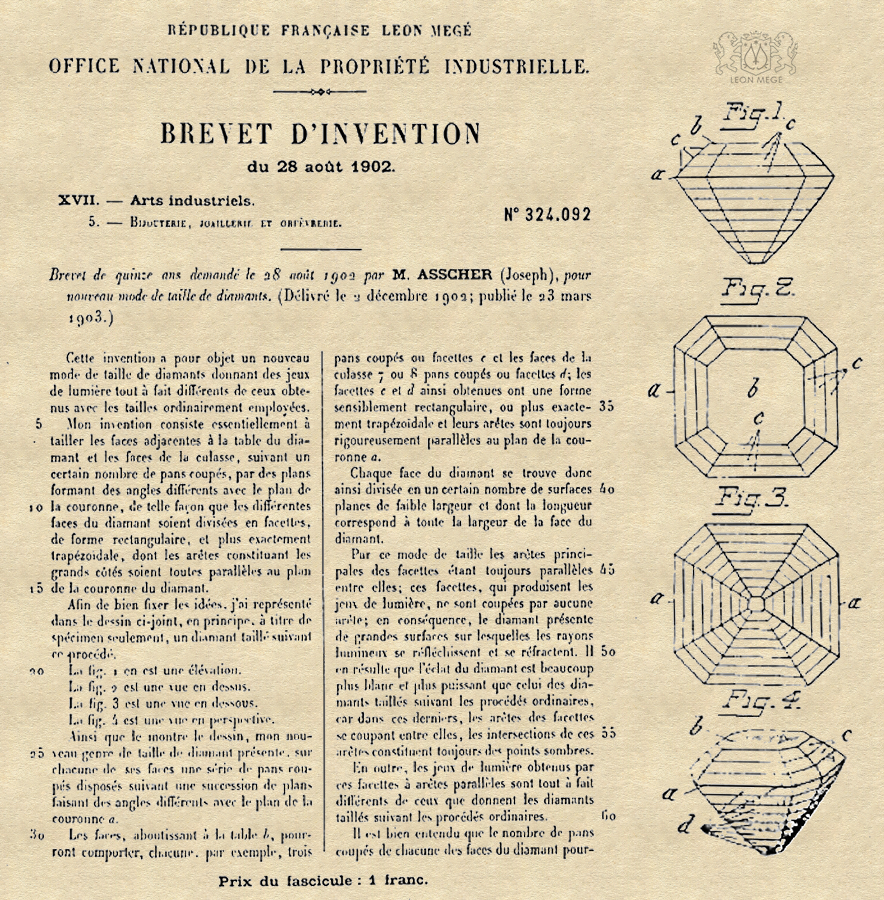

Asscher cut

is the number of Asscher facets, however the Royal Asscher has 74 facets.

An Asscher cut diamond is designed to bring out the clarity of a diamond. It is a special cut highlighting a diamond’s luminous presence and elegance. Its step facets radiate from a culet to the girdle in an X-shaped pattern.

All Asschers, including vintage and antique stones, are classified as cut-corner square step-cuts. A well-executed Asscher rivals a brilliant cut in fire and even in brilliance.

Varieties of Asscher cut

The modern “Asscher” is a trade misnomer for an emerald-cut diamond with a 1:1 ratio. It has only one common trait with a real Asscher—step-cut faceting. The modern “Asscher” does not have the charm and appeal of the classic Asscher cut.

The classic Asschers are scarce because rough yields are meager, and there is a limited demand due to high cost and relatively small size-to-carat weight ratio.

Authentic antique Asschers are extremely rare and found in antique jewelry. They are almost octagonal stones with a very small table, high crown, and deep pavilion.

True Antique Asscher

Joseph Asscher created the world’s first patented octagon-shaped step-cut diamond in 1902. An Asscher cut diamond seems to draw the eye to the center of the stone, to its magical depth, and to the source of its incredible fire.

It is an octagonal cut with corners almost as wide as the sides, a small table, a high crown, and a deep pavilion. The table of an antique Asscher is typically less than 50%, with a total depth exceeding 70%, and with evenly spaced facet steps.

Antique Asschers are hard to find and usually come from estate jewelry. True Antique Asschers are modern replicas of the antique cut. Due to their scarcity, both the antique Asschers and their replicas command premium prices.

Selecting and buying Asscher cut diamond

- It is not true that low color will make the flaws in Asscher more visible. All antique diamond cuts tend to mask the diamond color and make it less noticeable. Warmer-colored Asschers look more natural and face up whiter than expected.

- The recommended minimum clarity for an Asscher cut is VS1 because the inclusions are easier to see in step cuts.

- The most desirable Asschers have very wide corners. They are nearly octagonal, bringing them closer to the original historical cut.

- Shallow depth benefits the larger look, but true Asschers are, by nature, deep stones.

- Real Asschers are deep, with a total depth exceeding 70%. Spreadier stones with 60%-68% depth offer a better size-to-weight ratio.

- Asscher cuts are not cut for brilliance but for fire.

- Make sure that your Asscher cut diamond has a GIA grading report. This is the world’s most respected diamond grading laboratory.

Classic Asscher

The Classic Asscher is a contemporary take on the antique Asscher cut. It mixes the wide-corner, small-table, uniform-facet concept with the low-crown, shallow-pavilion proportions of a contemporary emerald cut.

The Classic Asscher cut produced today is not as deep as the Antique cut. Its table hovers at around 60%, its depth is between 65% to 72%, its crown is lower, and the corners are not as wide.

Classic Asschers are reasonably priced, but they are in a limited supply and require a trained eye and lots of time and patience to distinguish them from modern Asschers.

Modern Asscher

A square emerald cut diamond, often called Asscher in the trade, lacks the mysterious elegance and finesse associated with the true Asscher cut. These stones usually have tiny corners, a shallow less than 70% depth, and a large table exceeding 60%. To call this cut Asscher is, at minimum, misleading, and there is very little value in buying such a stone.

Royal Asscher®

Royal Asscher® is a patented cut with two additional pavilion steps sold at a steep premium. They are laser-inscribed with the brand logo and an identification number. The Royal Asscher® brand name is printed on the certificate.

Asscher's venerable name origin

The Asscher cut was created by the diamond cutter Joseph Asscher. His Royal Asscher Diamond Company Ltd. was established in Amsterdam in 1854. The extended Asscher family is renowned for being excellent diamond cutters and polishers. They work with hard-to-cut odd-shaped rough and are known to produce beautiful gems.

The Asscher factory once employed 500 people. In the old days, polishing wheels powered by steam engines were attached to long shafts with leather belts. The driving shafts ran the entire length of the building. Even after the introduction of electricity, the original shafts were retained.

Joseph Asscher

Joseph Asscher, the founder of the Royal Asscher Diamond Company, is famous for cutting two of the largest diamonds in history: the 995-carat Excelsior and the 3,107-carat Cullinan. Joseph was a third-generation diamond cutter in Antwerp who inherited the family business founded by his grandfather Isaac Joseph Asscher in 1854.

The story of Cullinan

King Edward VII contracted Joseph Asscher to cut the Cullinan diamond stolen by the British from indigenous Africans. Joseph studied the enormous piece of rough for six months. He finally notched a groove at a carefully calculated spot in preparation for the big moment. At precisely 3:05 pm, he took a shot of Jägermeister, mumbled something in Yiddish and hit the cleaver, and immediately passed out. After regaining consciousness, he learned that the stone split into three pieces, all according to plan. Was it stress or too much Jäger responsible for his fainting? We’ll never know.

Joseph fashioned the Cullinan into 21 gems, ranging from less than a carat to 70+ carat rocks. The stones cut from the Cullinan diamond, all flawless, are exhibited at the Crown Jewels collection at the Tower of London.

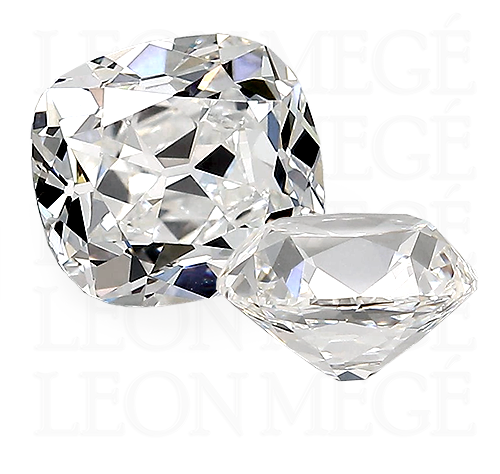

Classic or Antique Cushion

Classic (Antique) Cushions are rare, timeless, and sophisticated jewels. In the trade, they are known as Old Miners. The Antique Cushion’s high-contrast faceting mutes color perception, so it looks whiter than its modern counterparts. The Antique Cushion’s prized mix of fragmented brilliance and extreme dispersion is also unmatched.

Cushion Brilliants are essentially round brilliants with a pillow-like shape. Their pavilion facets originate at the culet and extend to the girdle in a star-like fashion. A stone loses its spot on the top of the cushion’s Mount Olympus and becomes Cushion Brilliant when it matches at least three of the following criteria:

– the table is over 53%

– the crown angle is over 40°

– lower halves are 60% or less

– the culet is slightly large

Cushion Modified combines radiant-cut facets with a cushion-shaped outline and soft, rounded corners. Modified Cushions have excessive brilliance without contrast, giving them a “crushed ice” look. Some facets terminate below the girdle. In places where the facets meet, they form bulges that complicate the ring’s construction and carry dead weight.

Antique Cushion

The traditional Antique cushion-cut diamond is a beautiful jewel. It has a pillow-shaped outline, soft, rounded corners, an open culet or a keel, a small table, and a high crown. The Classic Cushion comes with Old World flair and romantic appeal. Antique cushions are not necessarily old; Most antique cushions sold today have been recently cut.

The Antique Cushion was the dominant diamond cut for centuries until the advent of the modern round brilliant, which is uniform, scalable, and easy to make, sort, and use. Antique Cushions revived and recaptured the magic of the Golden Era.

Antique cushion diamonds have superior dispersion and radiate an abundance of fire when lit by flickering candlelight. They have an open culet, a high crown, and large facets—a perfect combination of sophisticated elements for a connoisseur seeking a diamond with character and pedigree.

Antique cushions are closer to step-cut diamonds in how they transform and return light. They don’t have the dreaded “crushed ice” look of modern cushions.

GIA classifies Antique cushions as Old Mine brilliant or Cushion brilliant depending on the crown, table, and total depth proportions.

Old European Cut - OEC

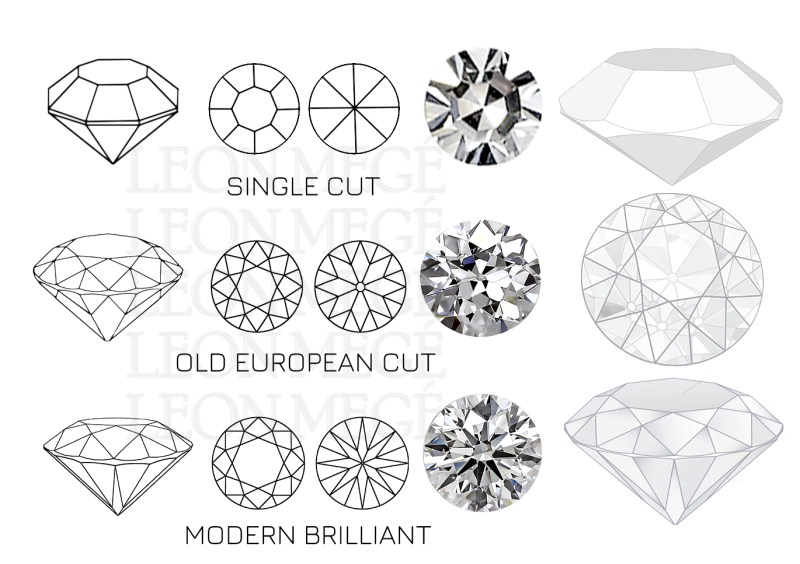

The Old European (or simply European) Cut is a vintage Round Brilliant. It became popular in the late 19th century when its predecessor, the Old Mine Cut, lost its Cushion shape and became round thanks to the invention of the bruting machine. The Old European Cut retained the rest of the Old Miner’s charms – the high crown, small table, and open culet.

The Modern Round Brilliant is a direct descendant of the European Cut. Both have the same round shape and 57 facets, not counting the culet. The proportions and angles have, however, changed drastically.

The current proportions of the Modern Brilliant inspired Marcel Tolkowsky, Henry Morse, and others to experiment with angles and facets, searching for the ideal round cut.

Today, Old European Cut diamonds are found in vintage jewelry. They usually have poor symmetry, often confused with old miners.

What makes Old European cut special? Like its predecessor, the Old Miner, the OEC features spectacular “inner fire” by design. When warm, flickering candlelight illuminated the 19th-century ballrooms, the Old European’s dramatic inner fire was a diamond’s most desired property. In later decades, when wearing diamonds outdoors became common, the emphasis shifted to cuts that maximize brilliance rather than fire.

- Old European Cut diamonds have small tables and relatively high crowns.

- There is always an open, often a large culet. The culet size may vary, but it is usually large enough to be seen with a naked eye.

- The Old European diamonds are not perfectly round. Cutting diamonds by hand often resulted in an off-round shape.

- The girdle of the old-euro is usually bruted. Its frost-like appearance is different from the clear faceted girdle of a modern diamond.

A Round diamond has to meet 3 out of 4 benchmarks to be certified as an Old European Cut by the GIA:

- A table size of less than or equal to 53%

- A crown angle of 40 degrees or more

- A lower-half facet length of 60% or less

- An open culet

GIA treats an Old European diamond as a fancy shape and does not evaluate its cut. However, Old Europeans are considered to be Round Brilliants in the diamond trade. The round shape is significantly more expensive than any fancy shape. The first brilliants, known as “Mazarins,” were introduced in the 17th century. Uniform diamond cuts did not exist until then, so each diamond had highly irregular shapes and a jumble of facets.

Before the invention of the diamond saw, a single piece of rough yielded just one stone. To maximize the yield, the European Cut was given a high crown, a small table, and an open culet. Skill and experience, rather than machinery and automation, give the Old European Cut a beautiful, organic, artisan look. The imperfections add character and timeless charm that only one-of-a-kind diamonds possess.

Old European Cuts are no longer produced. They are a prized find by collectors and history buffs.

The Transitional Cut

The Transition Cut also called the “American cut,” is a short-lived bridge between the Old European Cut and the Modern Brilliant. The experimental cut hosted a mix of modern and antique features in the same stone. The cut was invented in the 1870s by a Boston cutter and possibly a Red Sox fan. His name was Henry Morse, not to be confused with Samuel Morse, the inventor of the Morse code systems. Henry told everyone that a diamond’s beauty is more valuable than the rough yield. His goal was to find the most flattering proportions that return maximum light from inside a diamond. The diamantaires before him always strived to waste as little rough as possible during cutting. Henry, however, decided to go against the grain and waste as much rough as necessary to achieve the most sparkle.

Jubilee cut

The Jubilee diamond cut is usually reserved for large diamonds. The elaborate faceting empowers a diamond to shine spectacularly. Compared to the Round Brilliant’s 58 facets, the Jubilee cut features 88 (sometimes 80) facets. Because it’s not deep and has no culet, the Jubilee has a glittering effect second to none. It is one of the brightest cuts you can find and is also extremely rare.

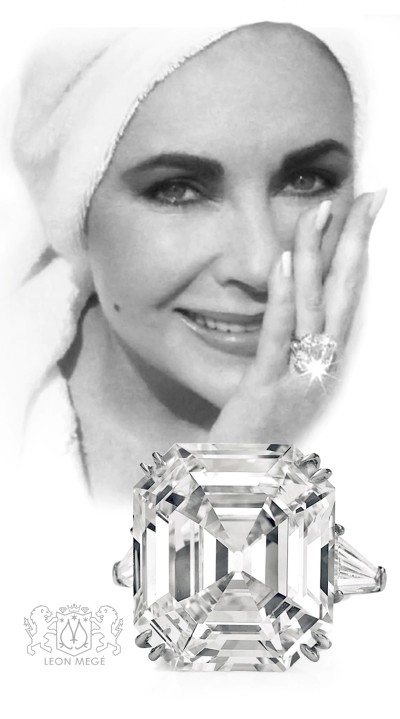

The Krupp cut

The traditional classic Asscher is a square cut with a length-to-width ratio of approximately 1.00 to 1.06. The Krupp cut is an elongated Asscher with a ratio longer than 1.1. The Krupp cut name comes from the emerald-cut diamond Richard Burton gave to Liz Taylor. Here is the diamond’s story.

In the early 1950s, German actress Vera Krupp, the trophy wife of a wealthy German industrialist, received a massive emerald-cut diamond with wide corners. Vera divorced her wealthy husband, kept the diamond ring he gave her, and moved to Las Vegas from Germany, breaking bad and partying around the town.

In 1959, the ring was taken from her at gunpoint during a robbery at her ranch. The FBI got involved because there was nothing better to do at the time at taxpayers’ expense and found the diamond at (of course, where else) a New Jersey grocery between mounds of mutz and gabagool. After the ring was returned, Vera became paranoid and pinned it to her bra strap at all times. When Mrs. Krupp passed away, the 33.19-carat diamond was sold to Richard Burton for $300k, who presented it to Elizabeth Taylor as a surprise gift.

The French cut

The French cut diamonds originated in the 14th century, named so because of their popularity in France. They evolved from the old Table cut. The Scissors cut is a variety of French cut with a slightly more elaborate faceting.

A French-cut diamond can be easily recognized by a rhomboid table turned 90 degrees to the diamond’s outline. The shape is usually square but can be rectangular or even trapezoid. The pavilion of a French-cut diamond is split into four plain facets, sometimes divided in half.

A French cut has a small table created by slicing one end of a well-formed octahedral crystal, and its edges have smaller facets added for extra brilliance.

French Cuts are a rarity because they are primarily found in antique jewelry. Currently, there is a very limited production, mainly from a rare type of diamond rough – the well-formed octahedral crystals. Unfortunately, the yield is low, which results in a higher per-carat price. Top jewelry houses quickly absorb the small quantities available, making sourcing French-cut diamonds on the open market nearly impossible.

Another factor limiting the broad adoption of French cuts is their lack of uniformity. The French cuts are mainly used as accents in groups called layouts, not individually, but the lack of uniform proportions prevents using them in calibrated layouts.

The French cut is a result of the evolution of the primitive Table cut diamond into a marvel of elegance. The French cut came into fashion in the 17th century and has been used in high-end jewelry ever since. French jewelers favored these diamonds, hence the name.

Antique-style French cut diamonds are produced using a well-formed octahedron rough. Modern French cuts are often produced by recutting baguettes and princess cuts, which have a low crown and a large table.

The French Cuts were extremely popular at the beginning of the 20th century during the Art Deco era featured prominently in the works of the top jewelers at the time. The Art Deco movement, with its emphasis on the pure geometrical forms, provided fertile ground for the wide use of French cuts in jewelry designs.

Princess and French cuts are distant relatives. They share a similar square outline. Facet’s arrangement, however, is completely different. While the French cut has charisma and elegance, the Princess cut is a square peg in a round hole.

Rose Cut

The Rose Cut is one of the oldest diamond cuts. It became widespread in the 1500s and remained popular until the early 1900s, when more complicated and precise cuts were developed. Picture a flat round diamond with a bulging pavilion and a giant table. Flip it upside down, and you’ve got a rose-cut diamond. It’s equivalent to a cabochon in diamonds.

Owing to their shape, carat-for-carat Rose Cut diamonds face up larger than any other diamond cut. This makes the Rose Cut an attractive purchase for those harboring a beer budget and a taste for vintage wine.

The crown of a Rose Cut is dome-shaped, formed by the facets meeting at the center. Because of its flat bottom and shallow depth, the rose cut reacts very differently to light than other diamonds. The absence of a pavilion results in washed-out luster and dull brilliance.

A rose-cut diamond crown has six triangular facets that resemble the petals of an unfolding rosebud. Perhaps having a drink can help you make the same connection. A conventional rose-cut diamond crown has six triangular facets arranged in a hexagon and small triangular facets completing the second row. Large stones have as many as seven or eight rows of facets.

Rose Cuts come in many shapes, although the majority are round.

Variations include the Briolette, a hexagonal Antwerp Rose, and a Double Dutch Rose, which resembles two Rose cuts united back-to-back. A Rose with a large table is called a portrait diamond. Rose-cut diamonds are timeless. They are a pretty cut that gives any jewel a unique vintage feel. Rose-cut diamonds can be used in any piece of jewelry and are exceptionally graceful in earrings, pendants, and necklaces.

The Rose Cut enjoyed a resurgence in popularity when Jennifer Anniston received a proposal with an eight-carat rose-cut solitaire, which sparked a short-lived renaissance. It’s still trendy and widely used in inexpensive fashion jewelry.

Rose-cut diamonds share proportion and faceting but come in many different shapes. The most common are round rose cuts, but there are also pears, cushions, and ovals.

Single cut

Single-cut diamonds are not for single people, just as the Full-cut diamonds are not popular with those full of, well.., you know what.

Single cuts, aka Eight Cuts, are small round diamonds with octagon-shaped tables, usually less than 10 points. There are eight crown facets and eight pavilion facets. Altogether, there are 17 facets, or 18 if you count the culet. Early single cuts were octagonal. They became round in the 19th century, thanks to the invention of diamond bruting lathes. In the 1980s, automated cutting made it possible to scale a full-cut diamond to a minuscule size. This automation made Single Cuts obsolete, and the Full Cut Brilliants replaced them.

However, modern precision-cut single cuts are still used in ultra-high-end jewelry and luxury watches, thanks to their superior brilliance.

The Story of Single cut

The Single Cut is one of the oldest diamond cuts. It is a very simple cut, essentially an upgrade from the Table Cut, which the Point Cut preceded. The Point Cut diamond is a naturally formed octahedron crystal that is polished but not faceted. With the advancement of diamond cutting techniques, the square Table cut gave way to the octagonal Single Cut.

Single Cuts rose to prominence in the 1920s. They were common accent stones in Art Deco pieces that extensively used antique-cut diamonds.

They are easy to tell apart – the Modern Single Cuts do not have open culets.

Antique diamonds were cut by hand under dim light, so they were malformed, ill-proportioned stones with uneven facets and poor symmetry. Some think this was the secret of their charm, but others disagree. Antique Single cuts are mostly used to fill up tight spots in vintage jewelry.

Modern Single Cuts are fashioned using high-precision technology. They have perfect symmetry and command a premium price.

As the diamond’s size decreases, its facets shrink so much that reflections blend into a single light point. In other words, they lose their brilliance, which is the diamond’s ability to blink. The facets of single cuts are three times larger than those of full cuts and provide superior brilliance when the stone sizes drop below 1.2 millimeters. Single-cut diamonds are used in luxury watches, pave in ultra-high-end jewelry, and as accents for vintage cut diamonds. They burst with brilliance and fire. They form a repeating pattern of facet reflections, giving micro pave a fabric-like texture. Using single cuts in modern bridal jewelry is unnecessary because they are more expensive and do not match the rest of the diamonds. Full-cut diamonds with 56 facets are a better option.

Antique pear

The first Pear Shape was invented in the mid-15th century by a Flemish cutter, Lodewyk van Bercken. The cut was a variation of a Rose Cut but with a point.

The True Antique Pear is not Briolettes or Rose Cuts. Instead, it has tables, crowns, and pavilions. Its point is usually blunted or rounded, and it has large open culets.

They are hard to come by; if you ever find one, do not let the marvelous stone out of your sight.

Moval

Often creating an illusion of a larger size, the Moval or antique marquise shape is the universal symbol of opulence and glamour. Moval is a gracefully elongated shape that straddles an oval and marquise. This rare and desirable diamond cut is typical of the Art Deco period.

Peruzzi and Mazarin Cuts

Created by Venetian polisher Vincent Peruzzi, the Peruzzi cut was one of the first “brilliant cuts” and is considered one of the oldest diamond cuts in existence. Peruzzi has 33 facets and is an ancestor of the modern brilliant-cut diamond. Peruzzi modified and improved the Mazarin cut by adding 16 more facets to create a diamond with superior brilliance.

The two obscure diamond cuts, Peruzzi and Mazarin, gave birth to the French cut through gradual transformations and improvements.

The early brilliant diamond cut created in 1650 was named after Cardinal Mazarin, who was very fond of diamonds.

Portrait Diamonds

A portrait-cut diamond resembles a thin sheet of ice with step facets surrounding a large, open table. The shallow cut was typically set over miniature portraits and tiled paintings. The portrait cut is similar to the Polki diamonds and has a similar faceting.

Polki diamonds originated in India long before the Jews of Antwerp developed modern diamond cutting. Polkis kept the original rough shape and had an unfaceted, polished surface.

Briolette

Europeans learned about briolettes in the 1600s when Jean-Baptiste Tavernier brought some from India to France. Louis IV, Marie Antoinette, Henry Philip Hope, and Persian and English royalty owned and admired diamond briolettes. Unfortunately, briolettes were the first casualties of recutting old stones into modern cuts, depriving the world of the ancient art form because the cut was deemed inefficient and wasteful.

It wasn’t until the Victorian and Art Deco periods that briolettes rose to prominence again, adhering to modern standards. Briolettes returned to the spotlight with a renewed appreciation for history, used by prominent designers spearheaded by Maestro Mege. Briolettes subtle beauty is proving to be timeless.